By letting go of writing code, you open yourself up to excelling as a manager.

I am a computer programmer.

I was one of those people who started coding at a young age – in my case, on a TRS-80 Model 1 in my school’s library. I loved the feeling of teaching the computer to do something and then getting to enjoy the results of interacting with what I built. Since I didn’t own a computer, I would fill spiral-bound notebooks with programs that I would write at home. As soon as I could get time on the computer, I would type it in line-by-line. When I learned that I could write software as a job, I couldn’t imagine anything else that I would want to do.

After university, I got my dream job writing 3D graphics code. I was a software engineer! I defined a successful day by the amount of code I wrote, the compiler issues I resolved, and the bugs I closed. There were obvious, objective metrics that I could use to measure my work. Those metrics and my job defined me.

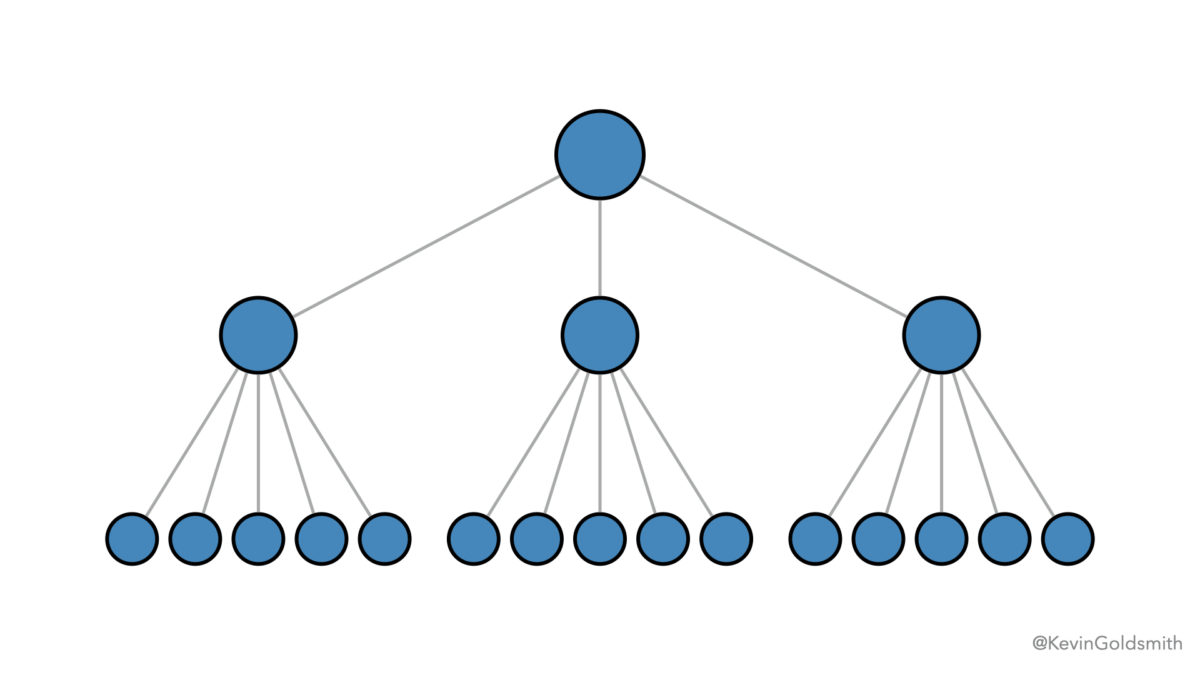

Today, I am a Chief Technology Officer, leading software development organizations. If I am writing code on the product, it is probably a bad thing. I now have to define my success by much fuzzier metrics: building good teams, hiring and training good people, setting multi-year technical strategy and vision for the company, collaborating with other departments, and setting and managing a budget. I may have a good day or a bad day, but I have to measure my success based on quarters or years.

My achievements are now always tied to the successes of others. Getting to this point wasn’t easy, but I wouldn’t have it any other way. It was a journey that took years, and the first challenge was understanding that coding was no longer my job.

Why is it hard to stop coding as our day-to-day work?

When I speak to engineering leads or managers working to grow into more senior engineering leadership levels, the question of ‘How much do you code?’ is very often raised. We usually have a hard time imagining that we can still be useful if we don’t code for a significant part of our time. Why is that?

We’ve been traditionally bad at hiring managers in the software engineering industry

Usually, companies choose development leads because they are the best, technically, on the team. I would guess that the reasoning behind this is that it’s assumed that the best developers are the right people to supervise their peers. This practice creates the impression that managing others is a promotion for a skilled developer when, in actuality, it is a career change away from what made them successful in the first place.

The worst managers I’ve had were very talented developers who hated having to spend time doing the boring stuff that wasn’t coding. They resented the time spent away from the keyboard and weren’t always good at hiding that fact.

Many companies now feature dual career tracks for technologists, giving them a choice to advance as an individual contributor or move into management. This choice of career is an excellent thing. It means that if you want to spend your days coding, you can do that without sacrificing your career. It also means that if you desire to find joy in leading teams and growing others’ development and skills, you can do that.

We fear becoming ‘non-technical’

We joined the technology industry to be close to technology. We fear that by moving away from coding, we will morph into the classic ‘pointy-haired boss’ – ridiculed by the people on our team and unable to understand what the developers are discussing. I won’t say this can’t happen, but it won’t happen on its own. It will only happen if you choose to avoid technology once you move into the management role.

As you take on broader leadership responsibilities, you will need to learn and understand new technologies. Moving beyond the specifics of your expertise is necessary for you to move up in management. I have managed developers coding in at least a dozen languages on the backend, frontend, mobile, operating systems, and native applications. I have also managed testers, data scientists, data engineers, DevOps, Security, designers, data analysts, program managers, product managers, corporate IT teams, and some other roles I don’t even remember anymore. It isn’t possible to be an expert in all those fields. I need to take the lessons from my time as a developer and use them to inform my understanding, help me learn new areas, and give me empathy for the people who work for me.

It isn’t that you will become non-technical. It is that you will become less narrowly technical.

As a new manager, we are often expected to continue coding

It is common to move from being a developer on a team to managing that team. As the new manager, this means you are still responsible for part of the codebase. Unless you immediately start leading a large group, your new role still requires that you spend a significant portion of your time coding. This expectation makes the transition to the new role more comfortable – but it can also be an anchor that holds you back from embracing your new role as your management responsibilities grow.

We still see ourselves as a resource that can ‘save’ a deliverable

As a manager, you are accountable for the results of your team. If the group is struggling to make a deadline, it might be tempting to jump into the weeds to try and help the team finish the project on time. While this is sometimes the right decision, it can also make the problems worse because the team loses the person who looks at the more significant issues and coordinates with other teams to get more help or prepare them for the delay.

Why do we need to stop coding eventually?

We don’t need to stop coding, ever. However, once you move into engineering leadership, it will need to become a smaller and smaller part of your job if you are working to lead larger teams or broaden your responsibilities scope.

I had led teams before I was a manager at Adobe, and I had always spent a significant part of my work week contributing code as part of the groups I was in. At Adobe, though, my team had grown to be fourteen people, with another four dotted-lined to me.

I had been the primary developer for a part of the project, and I took pride that I was still contributing important features to every release. However, my management responsibilities were starting to fill my work weeks. Between 1:1s, sync meetings with other teams, and other manager work, my feature development time was increasingly moving into my evenings and weekends. My features were often the last to be merged and usually late.

The company had two mandatory shut-down weeks. To work during this time, you needed the prior approval of a Vice President. The team was preparing for a release, and my features were still in the to-do column; I met with my VP to get his permission to work over the shut-down week. He asked me, “Who is the worst developer on your team?” I hemmed and hawed – I didn’t want to call out anyone on my team, and I hadn’t even really considered the question. Seeing my uncertainty, he answered for me. “You are! You’re always late with your features. The rest of the team is always waiting on you. If you were a developer instead of the manager, you would be on a performance improvement plan.” He was right. My insistence on coding was hurting the team, not helping it.

Taking on the lead role doesn’t mean you should stop coding immediately, but it does mean that your coding responsibilities should now be secondary to your leadership ones. There are other developers on your team, but there aren’t other leads. If you aren’t doing your lead job, no one else will. Similarly, your professional development’s primary focus should now be on your leadership skills, not your coding skills. You are moving into a new career, and if you don’t work to get better at it, you will find yourself stuck.

As your leadership responsibilities increase, you should transition your development responsibilities to other people on the team. This transition is good practice because delegation is an essential part of leadership.

How do you stay ‘technical’ when coding isn’t your job anymore?

As I said earlier, staying technical is a choice that you need to make. Hopefully, one of the primary reasons you chose to make a career in the technology industry was that you were interested in it, so this shouldn’t be a problem.

As I also said earlier, as you develop as a technology leader, your focus broadens as your scope widens.

The best way that I have found to remain a credible technologist for my teams is to be interested in them and their work. To do this, talk to the people on your team and take a genuine interest in the things they are working on. If a technology comes up in a meeting or 1:1 that you don’t know, add it to a list of things to research later. Then, dedicate time in your week to go through that list and learn about the technologies well enough to have your own opinions about them. This practice allows you to have further discussions with whoever mentioned the technology to you.

If you get interested in what you learn about the new technology, you may want to keep trying to understand it better; you may read more or embark on a personal project using it to gain more practical knowledge. As I said, it isn’t that you have to stop coding, it is that, eventually, it shouldn’t be your day job anymore.

By taking an interest in the technologies your team uses in their work, you deepen your empathy for them and expand your own knowledge. You’ll be able to discuss the work, ask reasonable questions, and make connections to other things happening in the organization and your own experience. This way, the people on your team know that while you may not be able to step in for them, you understand their work and care about it.

Success is defined differently when you lead people

The feeling of accomplishment that comes from completing a cool user story, deploying a new service, or fixing a difficult bug is significant. It is a dopamine hit, and just like other dopamine-inducing behaviors, it can be hard to stop.

Having a great 1:1 or leading a productive team meeting can also feel good but in a more esoteric way. As a team leader, you need to learn to perceive the success of making others successful. Success takes longer, but the feeling is more profound and more rewarding.

Having a release resonate with your customers, being able to easily justify the promotion of a developer that you have mentored, and having someone accept a job offer for your team, are all fantastic feelings. In the day-to-day, watching stories get completed, helping resolve the issues when they aren’t, and seeing people get excited about the direction you’re setting for the team can leave you feeling satisfied at the end of the day.

Being a technical leader doesn’t mean writing code every day

As you grow in your new leadership career, you will need to devote your time to mentoring, developing, and leading your team. As you spend less time in your code editor, you will find new challenges in strategy, clearing roadblocks, fixing broken processes, and new tools like HR information systems, slides, and spreadsheets (it isn’t as bad as it sounds). You will spend less time learning all the intricacies of a specific language or toolchain and instead learn about how systems interact, understand when to build vs. buy, and learn about entirely new areas of technology. And you can still code, but make sure that you aren’t the developer holding your team back.

[This was originally posted at https://leaddev.com/skills-new-managers/when-why-and-how-stop-coding-your-day-job]