New Photos, Summer 2022

Photos from Washington, Oregon, Texas and London

Sarcasm and vitriol wrapped in a twee bow.

Photos from Washington, Oregon, Texas and London

This is something I’ve been meaning to do in javascript forever but never bothered to figure out. JS can certainly do it, but it took me about 10 seconds to do it in PyScript. The code isn’t the cleanest, but it is very straightforward.

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta http-equiv="content-type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8">

<script defer src="https://pyscript.net/alpha/pyscript.js"></script>

<style>

:not(:defined) {

visibility: hidden;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello! My name is <span id="name-goes-here">Kevin Goldsmith</span></h1>

<py-script>

import random

names = ["Kevin Goldsmith", "????? ????????", "???????????", "?? ?????", "????????"]

el = Element("name-goes-here")

while True:

name = random.choice(names)

for n in range(0, len(name)+1):

el.write(name[0:n])

await asyncio.sleep(0.2)

await asyncio.sleep(5)

for n in range(1, len(name)+1):

el.write(name[0:-n])

await asyncio.sleep(0.2)

</py-script>

</body>A few notes:

This article is the final in my series on valuable performance reviews. This article discusses how to deliver the review and salary news to your report.

This article is the final in my series on valuable performance reviews. The first part addressed preparing for the evaluation. The second part covered writing the assessment. The third part explained how to make a salary recommendation. Finally, this article discusses how to deliver the review and salary news to your report.

Each review discussion is one of the most important meetings in a person’s professional life. The primary goal of the meeting is as a milestone in a career journey. You will give the person an understanding of the progress they have made and insight into how they can get to the next stage of their career.

All the work preparing and writing the performance appraisal can go to waste by delivering the review poorly. I have always found the review conversation the most nerve-racking for me as a manager because that is where you see the effect of your (hopefully) well-considered analysis on the person. And people are… people. The conversation is always a bit awkward, given the stakes for the person receiving the review—but from there, it can go in many unexpected directions. I’ve had tense, combative conversations with people receiving a very positive review. Conversely, I’ve had a very unexpectedly genial and optimistic conversation with someone accepting a poor review. Even if you know the person well, the review conversation can be challenging.

Common advice is to give precise feedback to the people who report to you frequently during the year. If you do this, the review itself should not surprise them, as it would be consistent with what you have already said. However, while someone may have heard the feedback, it is another thing to see it written on a piece of paper with a review “score” (if your organization does that) and a salary adjustment connected to that feedback. Even if you are confident that nothing written in the review is new information, the person receiving it may not feel that way.

The best method I’ve found for having these discussions go smoothly is to come to the meeting prepared, give the person time to digest their review before the dialogue, and structure the conversation itself.

If you have followed the spirit of the process in the previous articles, you have assembled, organized, and interpreted a lot of data to write the review. This data is also helpful for your preparation and during the conversation itself. Having the information to explain things further if there are questions or disagreements is valuable. Their memory or interpretation of events is sometimes very different than yours or that of their peers.

Read over their review again. Make sure you have the data at hand to support the evaluation you wrote in case there are questions.

If you think the discussion might be tense, you may even want to rehearse the conversation in advance with another dev manager or someone from your company’s HR team. I sometimes rehearse challenging messages in the shower, looking for the right way to say something. You may also prepare positive messages to find the best way to say something without ambiguity.

Think of the performance reviews you have received during your career. Both the good and bad. What made them stand out to you? Was it the review itself or the discussion (or lack thereof)? While the anticipation and the initial excitement of the evaluation are finding out about a promotion, raise, or bonus, and knowing that your hard work was recognized, the thing you will remember long after was the delivery of the information and the discussion that followed.

I’ve received at least fifty reviews since I started working. I don’t remember the numbers or most of the review scores. Still, I remember the manager who hadn’t put any thought into the process, the one who made promises review after review that they never kept, and the assessment where a manager made statements that were demonstrably false and, when shown evidence to the contrary, threw up their hands. I also remember the great conversations I had with the best managers I worked for that made me proud of what I had accomplished and excited about what more I could do (and how they would help me).

While you may be nervous about the conversation, the person you speak to is even more so. For you, it is the conversation that is scary. For them, it is the implications of the discussion on their livelihood. So come to the dialogue with that understanding and empathy for their position.

There is always the question of when to let the person read the actual document. Over the years, I have tried it three different ways:

The method that seems to work best is to give the person the assessment to review several hours before the review discussion, saving the actual numbers for the conversation.

When you give the person time to read and process the review document before the meeting, it allows them to prepare for the meeting. It takes some of the person’s concerns away because they know what to expect in the conversation itself, which makes the conversation less stressful for them. If they disagree with the assessment, it gives them time to prepare any argument/evidence they wish to present, making it feel less like an ambush. By sharing the review in advance, I have found that the conversation itself is often more substantive and valuable.

While you both know why you are there, it is good to start the discussion with some of the broader contexts around the review process and anything around the company’s performance that will be relevant to the meeting (like a limited raise budget in a tough economic year). But, unfortunately, that broader context often gets lost in the review conversation itself, which can lead to confusion or misunderstandings.

If you’ve given the document to the person in advance, they will join the meeting with an idea of what to expect in the conversation. However, they will still be wondering about the salary numbers. While you may be talking about other things, until the person knows what their salary change is, they will wonder about it. To make the conversation more valuable, I like to share the salary change information or promotion early in the conversation. Once the person knows the most critical information they will receive, they can focus on the more extensive discussion about career development.

Discuss each section in the assessment together to make sure that there is a common understanding and agreement. Now is when you might share more details or data around your statements if needed. Do not just ask, “Do you agree with this section?” Instead, make sure they understand your comments, that you have answered any questions they have, and that they either concur with your assessment or at least appreciate your perspective and the data behind your conclusions.

If the review conversation is a checkpoint along a career, it is essential to help the person understand where the next checkpoint could be. It is vital in the review conversation to talk to the future and reflect on the past. Now is an excellent opportunity to give hope and support to someone who had a problematic review cycle or inspire someone who has been doing well to achieve even bigger goals.

Hopefully, you have been having regular discussions about the person’s career aspirations. The review discussion is the right time to confirm their goals and discuss how you can help them achieve them. What opportunities can you present to them that will help them grow professionally between this discussion and the next review discussion?

Be very careful about making promises that you can’t keep. There are many things beyond your control in the review process, like the raise budget, the stock pool, company performance, global economic situations, or a final promotions approval. Even if you had all those things within your control now, you might move on to a new role or new company by the time of the following review. If you make a promise and cannot keep it, you will demoralize the person and lose their trust. So choose your words carefully when talking about the future.

Within a few days of the discussion, write the person a note confirming any statements from the conversation, the answers to any questions you didn’t have during the dialogue, and the agreed-upon growth plan. If you have a shared agenda for your 1:1s or a list of topics to discuss, make sure that you regularly review any growth plans by adding them as a discussion topic.

From time to time, someone will decide that your interpretation of the data is incorrect and, therefore, your review is wrong. When this happens, go over the person’s data you collected for the appraisal. If they have some information you didn’t receive in the process that causes you to reconsider, don’t promise them that you will change the review. Investigate the new information and if you want to change things, discuss it with your manager. This kind of late change rarely happens, however.

If they continue to refuse to accept your assessment, invite them to sit down with you, your manager, and a person from the people team to discuss it. You want the person’s concerns heard, but if they don’t have any new data, you also want someone in the conversation who will support you.

People will occasionally believe that the salary discussion is a negotiation. I have heard that this is common in a few cultures, but it is not generally done that way. As I discussed in the previous article, the person’s new salary is arrived at as part of a long process, and there isn’t much—if any—flexibility by the time you are delivering the review to the person.

You generally can’t change their salary autonomously, so if you agree to reconsider and then you can’t change the number, you look ineffectual as their manager. Also, changing their salary will encourage others to try to negotiate in the salary review discussion (the word always gets around when something like this happens).

If someone is unhappy with their raise, discuss what they could do during the next review period to justify making a more significant raise recommendation. But, once again, don’t promise anything!

If someone was expecting an entirely unrealistic raise, you might want to share with them a bit about how the salary review process works and help them understand what normal looks like.

Occasionally, in the salary review discussion, someone will tell you about their friend who got a 50% raise. They will also tell you about an article they read that says many companies are giving considerable raises to retain employees. Given how charged salaries are as a subject and how competitive the technology industry is for good talent, much disinformation about salaries is constantly circulating.

When faced with these stories, it is worth discussing your company’s salary benchmarking process. Help the person understand that there will always be outliers and unusual situations, but express that those are the exception and not the norm. It is also worth discussing the non-salary aspects of your company that make it an exciting place to work. Companies often look to salary as their only employee retention tool when it is hard to retain employees because of their culture, lack of growth opportunities, or uninteresting projects.

In this article, I talk about the many ways the review discussion can go wrong because that can make the whole process scary for many people. It is good to be prepared for the conversation to go in a challenging direction. However, if you have been open with people about their performance and regularly given them feedback, and you talk to them about how you will help them improve their performance, the tough conversations are few and far between.

I usually end the performance review process proud of what each person has achieved and excited about helping them reach their potential. That is my hope for you as well.

Thanks to Laura Blackwell for editing assistance

This article is part three of my series on writing valuable performance reviews. The first part is about preparing for the evaluation. The second article discusses writing the appraisal. This piece will help you make a fair raise recommendation. The final part gives you tips on delivering the review.

Determining compensation is a crucial part of performance management. I fully believe in the Autonomy, Mastery, and Purpose trio for motivation outlined in Daniel Pink’s book Drive. However, experience has shown me that even people who have all three of the trio still expect performance in their role to result in more significant compensation.

Aside from hiring or firing an employee, compensation decisions are the most important decisions a manager can make. The decision is significant because the basis for next year’s compensation is this year’s, especially if you stay at the same company. A manager’s mistake in remuneration can result in a significant difference in lifetime salary for someone. Therefore, the compensation change recommendation must be highly considered and fair.

In some companies, the manager creating and delivering the performance review has little input in the compensation decision. If this is your situation, it is still helpful to understand how salary works at other companies, since you may hire people from those places. It is also beneficial when you are responsible for that decision after a promotion.

Many junior managers have unrealistic expectations around what can be done with compensation because they don’t understand that it is part of the greater corporate budgeting processes. As a result, they imagine an infinite pool of money to draw from for raises.

Every company does its budget and compensation processes differently, but there are common aspects across all the companies I have worked at. One generally true statement is that larger companies will typically be more fixed in their processes and make exceptions infrequently.

The compensation budget is part of the larger company budget, which is agreed upon with the board of directors at the start of the year. An essential measure of the ability of the senior leadership team is their capability of working within the constraints of this agreed-upon budget. This budget objective means that at the most senior levels of the company, someone is keeping an eye on the total salary budget for your organization and will work very hard to make sure that it is not over budget. There is a target salary budget for your team based on the team’s current salaries and the board’s agreed-upon raise budget as a delta.

Your manager will recoup the difference from another team if they allow you to go beyond that budget. Does this mean you shouldn’t go over budget if it is warranted? No, but it means you need to have realistic expectations about what is possible.

To avoid the budget constraint challenges, line managers in some organizations do not have salary recommendation responsibility.

You receive:

If you don’t receive all this information, you should request it. It is vital for the decision-making process.

You make an initial recommendation for each team member, which you send to your boss. Your manager combines your proposals with those of your peers, adds in their own direct reports (including you), massages the numbers somewhat, and passes it to their boss, who does the same. This process continues to the CEO.

A few weeks (or months) later, you receive the final salary numbers for all your reports to communicate to them, either as part of the performance review or separately. Sometimes the numbers are identical to those you recommended; sometimes they are different. Sometimes your boss knows why the numbers are different, and sometimes they do not.

Salary is just one part of a compensation scheme; stock, bonuses (if your company has them), commissions (usually only for the sales team), and benefits are all part of how a company attracts and retains its employees. Each of these elements has a different purpose.

Salary is a direct measure of employee performance. It is to reward someone for doing a good job. Employees who are “high performers” are paid more than others in the role whose work isn’t as valuable.

Equity, in the form of stock grants or options, is usually seen as a measure of employee potential. Since these vest over time, they are an incentive for an employee to stay longer. Therefore, you want employees who have a high potential to stay and grow at the company. Some companies also use equity to offset salaries, since the immediate cost to the company is less.

Benefits are often overlooked because they are given equally to all employees, but they can be vital to employee retention. For example, if an employee is interested in developing their skills, letting them know that the company can pay for additional training is a significant statement and may counterbalance a raise that they are not happy with.

When making recommendations around employee compensation, take all the aspects of your company’s compensation plan into account. Different elements will be more important at various times to your employees.

Some companies, notably Buffer and Gitlab, have adopted fixed formula models for employee compensation and transparency about those models. Company founders designed these models to be fair and reduce bias. I think there is a lot of potential in these models, and the people I know at companies that have them are fans.

Typically, the companies that do fixed compensation systems adopt them very early (instead of switching to them later). The companies are transparent about their compensation, which is critical with a nonstandard model. As such, people generally self-select into those companies. The mechanics of switching to that model seem very difficult to me.

It is worth paying attention to companies using these systems to see how they scale and grow and see if they become the norm.

The significant part of the fixed compensation systems is that they take the bias and subjectivity out of the raise decision. The bias is all built into the decisions that created the original model. You should strive to be objective and fair for the more standard processes. You should validate the reasoning you use with your manager and peers to ensure that the organization uses a consistent rationale.

Where is the person’s current salary within the salary band? Does that current salary make sense, given their past performance? Has the band gone up significantly since the last salary review period? Where do they sit relative to their peers in the same role/level doing similar quality work?

Are they meeting your expectations or exceeding them? Not achieving them? What has been their trajectory over the last few periods? Are they gaining momentum? Losing it?

If you are promoting the person, you should be gauging them against the bands for their new level. Unless the promotion is long overdue, or the person was very highly paid relative to their peers in their previous level, they should be coming into the lower part of their new salary bands. Placing them in the appropriate spot in the salary band gives them ample room for raises as they grow into their new responsibilities.

Some of your team should be over that, and some should be under. Your boss will tell you if they expect you to achieve a budget target or not. Even if you anticipate not to come in exactly on budget, you shouldn’t be wildly off it. Now, based on the target budget, the person’s current salary, and their performance, put in your initial number for them.

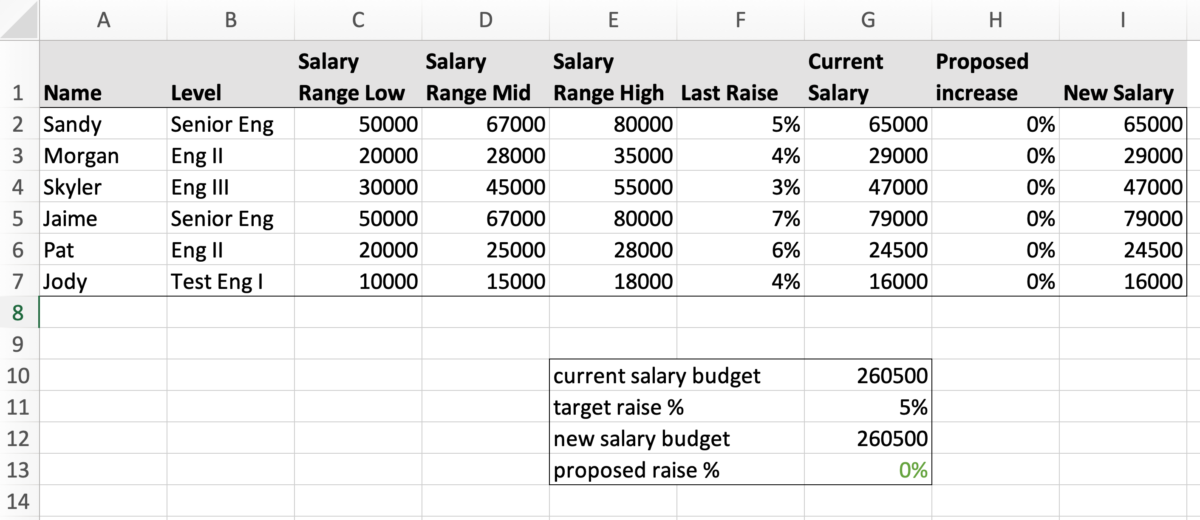

I generally have something like this (and create it if I don’t get one from the HR team).

A spreadsheet helps you look at your recommendations for people relative to one another, and it enables you to understand what you regard as the target for your team.

Don’t pay attention to any of the other data while you do this. If it helps, you can hide any rows or columns that you are concerned may throw off your judgment. You can also enter it into another tab if you prefer.

After you have done your first-pass numbers for everyone on your team, you can see where you are relative to your budget. You should also look across the team to ensure you are using consistent logic. It is better to look at percentages rather than salary amounts at this stage. Are the overperforming people relative to your career rubric getting more significant raises than those underperforming or merely meeting expectations? Are the raises going to underperformers in alignment with their performance?

One way to approach this is to think about the raise conversation relative to the performance conversation. Are you saying the same thing with both? For example, a sizeable raise completely blunts a stern message to someone underperforming. Similarly, a slight raise blunts any positive message in the performance review for an overperformer.

Are you over budget? If you are over by a relatively small amount, and your manager has not asked you to be right on target, you may be ready to show them the numbers for their input. On the other hand, if your manager has asked you to be right on budget, then you will need to make some adjustments.

If you are significantly over budget, you can use one or more of several techniques for bringing your numbers down.

Applying the same amount of reduction to all your recommendations keeps them the same relative to one another.

If someone is significantly underperforming, recommend no raise rather than giving them an insubstantial raise. Receiving no raise will ensure a difficult review conversation, but it will reinforce the underperformance message.

When given their new salary information, people will look at the percentage and the new salary number and remember one of them, the salary. They won’t recollect the exact wage; they will round the number in their heads. Take advantage of that to get some extra headroom.

Let’s look at one of our fictional employees, Sandy. Sandy has done very well this year, and you want to reward them with a big raise. Your first idea is a 9% raise, which will give them a new salary of 70,850. After doing the rest of the raises, you are more over budget than your manager is OK with. Since Sandy is your second-highest paid employee and is getting a big raise, you can give them a slightly smaller amount, and they will likely not miss it. Instead, if you gave them an 8.46% raise, that would give them a new salary of 70,500 (a nice round number), and it would save you 350. If you needed more room, 70,250 or even 70,000 are still big raises from their initial 65,000, but are only minor percentage differences from your initial idea.

The rounding trick I mentioned above is also helpful if you work against budget constraints, but you want to give more significant raises to those on the lower end of the salary spectrum. A small percentage change for a well-paid person can be a very substantial percentage change for someone who is less well-paid. I call shifting small percentages from higher-paid to lower-paid employees Robinhooding.

The answer to this question will depend on your organizational culture and norms. If this is your first time making salary recommendations, you might ask your manager for guidance. If all your peers come in over budget, and you are under, you may either look fiscally responsible, overly critical, or like an obvious place to find more funding for your peers’ excesses. You don’t want your team to suffer for other managers’ inability to meet a budget.

If you are significantly under budget, you may want to reexamine your recommendations, as this would indicate a seriously underperforming team.

Are your recommendations saying something you do not intend? For example, is there one group getting the majority of the large or small raises? Look for your own unconscious biases appearing in the numbers. Once you are fully satisfied that your recommendations indicate the performance of the individuals on your team, submit them to your HR representative or manager for the next phase of the process.

Your manager may want to review your recommendations with you, or with you and your peers together. Your manager must ensure that each report uses consistent guidelines for their recommendations. They may do this independently or may pull all their manager reports together for a more extensive session (at a previous company, we called this the “Battle Royale” ).

Come prepared when it is time to review your recommendations with your manager or peers. Preparation should not be problematic if you have followed the recommendations from the previous articles. The more concrete examples you can provide to justify your proposals, the better.

Your manager will incorporate the input from you and your peers into a larger version of your spreadsheet. They may need to modify some of your numbers to make their numbers work. Your manager will then do a similar review with their peers, and it will go up the levels of the organization, potentially to the senior leadership team. The more information you give your manager, the easier it will be for them to preserve and defend your recommendations. The information you provide them will also give their manager more information.

Once there is agreement on the salary changes for the organization, the finance team updates the numbers in the payroll system. You then receive the final numbers to pass on to your employees.

I discuss the salary and performance review conversations in the following article.

The four parts of this series are:

Thanks to Laura Blackwell for editing assistance

This article is the second in a four-part series on writing performance reviews. In the previous article, I wrote about preparing data for the assessment. In this article, I talk about filling out the review form. The next article discusses making salary recommendations. The final post covers delivering the review.

Before you begin to write your review, make sure you have the role and level definition for the person’s current role and level. You should also have the description for the job at the next level. If you followed my suggestions in the previous post, you have the folder with earlier reviews, notes from 1:1s and project meetings, the peer feedback, the person’s self-evaluation, and your notes on the work output. Your company’s performance review form and supporting process documentation are necessary as well.

If you followed my advice from the last part, you have assembled a large amount of data. You will now go through it all to evaluate the person’s performance relative to the standard. You may find it beneficial to highlight essential information in the documents as you review them or copy/paste them into a new file for easy reference.

If you can, do your review in one sitting. This process helps you build an understanding of the person’s performance. You are creating a context with as much data as possible, so keeping it in your near-term memory is beneficial. If you don’t have enough time to do this in one sitting or think you may be interrupted, take good notes that you can review after a break.

As you read over the data, you should be consciously building a narrative of the review period. Each person will have some highs and lows, but patterns of performance should emerge. After reviewing the data, you should have one or two specific messages to convey to the person about their performance. That is the goal of data accumulation and evaluation.

First, read through the review form, making sure you understand the expectation for each question. Then, if you are in doubt, use the company documentation on the process. Get clarifications from your HR partner if necessary.

Make sure you understand the person’s role expectations at the current level and the next level. The current level documentation covers the performance expectations the person should meet now. The next-level documentation is helpful for you to recognize performance beyond expectations.

Read all the previous reviews the person has received at the company in chronological order. This review will help you see patterns and trends, and goals met and missed. The essential evaluations are the most recent, especially any from the last couple of years. Take extra care reading these to remind yourself of prior performance discussions (if you wrote them) and understand the current development areas.

Suppose the person is new to your team, or you are a new lead for an existing group. In that case, occasionally, you will read prior reviews and realize that the previous manager used a very different approach to performance than your own. Ideally, everyone is evaluating against the company’s career pathing rubric, but sometimes it is applied differently. In this case, you may need to prepare for some challenging conversations.

You might choose to treat this review cycle as a transitional one, giving people time to adjust to your management style. If you do that, make sure they understand how future reviews will work differently.

Scanning through your messages from the review period will help remind you of any events, successes, or challenges that you may have forgotten about during the review period.

A reminder from the previous article: a person’s code contributions do not reflect the sum of their contributions. Senior developers may contribute less code because they are more efficient or spend time helping other people. Look at code reviews, bug notes, documentation, Architectural Decision Records, or anything else that will demonstrate contributions to the team’s projects.

By this point, you will have started to build the narrative, identified some possible key discussion topics, and formed opinions on the person’s performance. You likely started the process with ideas already, based on your interactions with the person over the review period. The views you bring at the start of the process aren’t necessarily incorrect. Still, they may be untrustworthy because of recency bias, affinity bias, or the person being very good at promoting their accomplishments (or taking credit for others’ work).

Now you will start to review the more subjective data. Does what you find conflict with or reinforce your existing viewpoint?

Peer evaluations can be problematic. First, people can be tempted to cheat, colluding with their peers. Second, many people don’t want to criticize their co-workers. Third, they may worry about how their comments reflect on themselves. For these reasons, you will want to read between the lines when reading peer evaluations.

As you read through the peer comments, look for examples that support or challenge the narrative you have been building. If you find many things that challenge your message, you may reevaluate your opinions.

When people are evaluated based on something they produce, they naturally tend to create a narrative that accentuates their positive contributions and minimizes their negative ones. It isn’t necessarily deceptive; it is human nature. Therefore, I always read the self-evaluation last. I don’t want it to influence how I evaluate all the other data. However, the self-evaluation is still relevant because it is the person’s view of how things have gone—their side of the story.

There are a few things I always look for when reading this document: Are there good explanations for some challenges they had during the review period? How aware are they of their challenges and strengths? Are there any comments that might be relevant for the reviews of others on the team? Where are they interested in growing? Finally, is there anything that you can do to support them better in the following review period?

Having reviewed all the data, you are now ready to write the review. You have one or two messages for your narrative as well as the data to support it.

One of the biggest mistakes people make when writing a review is trying not to be too negative or too positive. Particularly problematic is using the “compliment sandwich” or vague language to avoid a challenging conversation when delivering the evaluation. Another mistake is creating a “balanced” review by overemphasizing small challenges or successes to offset a too positive or negative narrative.

When someone reads your review, they want to know if they are doing well or not doing well. If the person doesn’t know after reading the evaluation, it is not helpful to them. In addition, they should have a clear connection between their review and their salary adjustment.

Often, I see inexperienced or poorly trained managers produce reviews for their teams that are uniformly good. “Everyone on the team is doing great!” they say. However, even on the highest performing teams, some members will contribute more than others during a review period.

Universally positive reviews are a signal that a manager is either not promoting team members (so they are all overperforming relative to their level), not paying attention (they are missing things), not challenging the individuals on the team, or setting their expectations too low. Exclusively positive reviews are a signal about the quality of the manager more than the quality of the team.

Yes, you can have a great team where everyone is contributing well. However, each person still has strengths and weaknesses compared to the role/level rubric. You need to understand that you aren’t doing your duty to your team or the company if you don’t evaluate people objectively.

Suppose you want to emphasize that the individuals on your team are outperforming individuals on other teams (often crucial if your organization “stack ranks”). Make that point in the accomplishments noted from each team member. Rating your team universally high just looks like you are trying to game the system.

Something I see less often is a manager rating their team uniformly poorly, usually when a new manager joins an existing group. When I see this, I wonder if the manager is trying to make a statement about the team they inherited, if they are setting the initial base level low so they can show improvement, or if they are setting their bar way too high. As with overly positive reviews, this behavior is often more indicative of issues with the manager than the team.

If you find yourself compelled to give poor ratings to the entire team, challenge yourself to defend your ratings by comparing each person’s accomplishments against the rubric. Are you being too harsh in your judgment or can you justify each of the ratings? Use a “five whys” exercise for each person’s rating. Do find unique causes for each person’s poor performance, or does it all come back to you?

As you fill out the form, answer each question to support your message for the recipient. Answer each question with a statement, then provide data that supports your answer.

Avoid phrases that ascribe intent to the person’s actions. Instead, speak to what they did and the measurable effect it had. Do not use expressions like “I think” or “it seems.” These phrases show a subjective interpretation. You want to ground your assessment in facts. Being fact-based avoids any disputes about the review if the person does not like the result.

Identifying areas of growth for someone is helpful for them. However, if you are being straightforward, a review for someone underperforming can be demotivating. Rather than finding positive things to balance the assessment at the risk of making it less forthright, you should focus on how you will help the person address their performance issues. If the performance is so poor that the person will put on a performance improvement plan, be specific on what they need to change to move off of the PIP.

What are the next steps for those on your team who are overperforming against their role/level? What opportunities can you identify for them? What new responsibilities? Are they on a path for promotion? Where should they focus on continuing their growth?

People who are doing well aren’t usually satisfied with being recognized for their work (although it is imperative to acknowledge their work). They want to know what is next for them. They want more responsibility, more challenge. They want to expand their skills. How will you help them do that in the next review period? They will want to know.

Most of your team will not be underperforming or overperforming. They will be doing their jobs well. The work that these folks do is essential. They are how the team’s work gets done. Recognize their strengths and weaknesses and tell them how you will support both.

Some are happy to continue to deliver solid performance, and unless your company has an up-or-out culture, this is fine. People will have natural ebbs and flows in their careers.

If the person is ambitious, focus on opportunities for their growth and be clear on what overperforming requires. The company’s career pathing rubric is a reference to show them what is needed.

Once you have completed all the performance appraisals, go back and review them. Look for patterns in your assessments. Look for potential unconscious bias. Try to read them as your manager or some future manager of the person would. Are you providing enough information to justify your statements? As this process can take a long time, does it seem that you put less effort into later reviews when you got tired?

Before submitting them to your review system, make sure that you are happy with them individually and as a group. If you have time, you may want to wait a few days after writing the last review before you reread them to give yourself some space.

If your review process includes a grade, ranking, or nine-box classification, ensure that your performance reviews support where you put each person. Also, look to see what the distribution of rankings or grades makes sense. For example, are your recommendations so clustered that it doesn’t seem that you are using good judgment? Does your review justify your choices?

In some companies, salary change recommendations are part of the performance review writing process. It runs as a separate process in other companies (usually near the performance review process on the calendar). Line managers do not have direct input into compensation changes at some companies.

However compensation changes work in your company, it is good to understand how to make compensation decisions/recommendations for your team. That is the subject of the next article in the series.

Thanks to Laura Blackwell for editing assistance

It’s December, and that can mean only one thing. For many of us, it is now—or soon will be—time to write performance reviews for our team. Writing reviews can be daunting for many, especially those with large groups or little experience. There are some things you can do that will make the process less onerous, no matter what format or schedule your company has.

It’s December, and that can mean only one thing. For many of us, it is now—or soon will be—time to write performance reviews for our team. Writing reviews can be daunting for many, especially those with large groups or little experience. I often hear managers (even senior leaders) bemoaning the effort it takes to write the reviews for their group members. However, there are some things you can do that will make the process less onerous, no matter what format or schedule your company has.

I’m going to break this subject into four parts:

The rationale we used to hear for performance reviews is that they are for the employee to know how they are doing, to give them helpful feedback on what they are doing well and where they need to improve. Today we try to provide this feedback often, throughout the year. I often tell the managers on my teams that there shouldn’t be any surprises in the performance review. It should instead be a summing up of the feedback that the person has been receiving all along.

If we give feedback throughout the review period, why do we need to do the performance review? It is for the company and us almost as much as it is for the person receiving it. Ideally, we maintain a narrative across the year with our feedback, reviewing months of our notes and prior communication before each one-on-one. All too often, the larger arc gets lost in the whirlwind of work. The feedback we give is usually very transactional about what has just occurred. If there are significant overarching discussions, we may be able to tie the feedback to that, but often the narrative gets lost.

The review is a chance to look across all that has transpired over a much lengthier period than the time between one-on-ones. It is a chance for us to take stock and find new patterns or trends that we may have missed. To look at the bigger picture and then build a shared understanding of that picture with the team member.

The review is also for the company because the company keeps a record of employee performance to justify bonuses, promotions, salary increases, and stock offerings. It is also vital to have a history of performance for a new manager if you move on from your role. Sometimes you will move to a new job, or the employee will move to a new team. When that happens, all the shared understanding you have built up is lost unless it’s written down. An employee who has been working years towards a new role may be set back significantly if their new manager doesn’t understand the efforts they have made over time and is looking only at what they see in the present moment.

A well-written review is a valuable document for the person receiving it. First, it is a checkpoint for them to refer to as they work towards their career goals. Second, it is a useful document for you to help them on their career path. Third, it is a favor to their future managers at your company. Finally, it is a critical document for the company and your manager to understand how to manage compensation for the person.

Often writing reviews seems like a great deal of work because we wait until our company’s official “kick-off” of the review period. The people/HR team lets all the managers know the schedule, does a few meetings to discuss/update the process, and opens the forms for managers to enter data. If you wait for that moment to begin preparing your reviews, you may find yourself spending a lot of nights and weekends trying to get your evaluations prepared, since your regular work continues during this time. In the past, I’ve spent more than a few sad weekend days sitting in a ski lodge huddled over my laptop, writing reviews while my family was out on the slopes having fun.

Your company may adjust the dates slightly, but you can be confident that reviews will happen around the same time each year. When the dates are announced, you should be prepared. If you are incredibly diligent, you may be collecting and organizing data for your reviews year-round. If you haven’t done that, you can start reviewing, amassing, and organizing supporting data as review time approaches so that you don’t have to struggle and potentially miss things. While the format of the reviews in your company may change periodically, the general things that are measured likely won’t.

As I start my preparation, I create a folder on my computer for the review period and a subfolder for each person. In each folder, I assemble all the documents and data for the performance assessment. I prefer to keep local copies because it is less likely that I will accidentally share the folder or file. To focus, I often go offsite to work on reviews, and sometimes these places have sketchy connectivity. Having the documents stored on my computer has functioned well for my process.

I used to store all my notes in Evernote organized by meeting (for recurring meetings) and tagged with the people in the discussion. This storage approach made it easy to find all my notes for each person to track what we spoke about across the review period. However, during the pandemic, I switched to paper notebooks. Now I keep an index of which pages people appear on. This index makes it easy to find all my notes referencing someone.

As I review my meeting notes, I assemble meaningful comments or things I notice into a new document in the person’s folder to organize my data for the review. I include where I got it from for each item in case I need to go back to the source.

I always download copies of any previous reviews for the person in the system and put them in the folder. It is vital to remember our prior review conversations and see any reviews before they reported to me. Reading previous reviews helps me understand the different challenges and strengths they have had and understand their career story at the company so far.

Occasionally, things come up and are resolved between one-on-ones or meetings, so they don’t appear in your notes. I scan over the e-mail and Slack exchanges I have had with the person during the review period to see if I missed an event in reviewing my meeting notes.

I copy/paste these exchanges into the notes document in the person’s review folder, or summarize them there.

Your company may include a formal peer-review element in your performance reviews process. However, if it isn’t part of the company process, you will still find it valuable to ask for peer review feedback. The first step is to list the people you would like to ask for feedback, so you are ready. You may also write the template for the peer feedback request to prepare you to send them out.

I’ve noticed that in companies with a formal peer feedback process as part of their reviews, people quickly become inundated with feedback requests. Your chance of getting valuable (or any) feedback is greatly improved if you send the request early, before people have feedback fatigue.

If you know that peer feedback will not be part of your company’s process, you may still want to send out the feedback requests early to get the responses with enough time to follow up if there are questions. However, make sure that you specify a date by which you would like the feedback returned, and don’t make that date too far in the future, or people will put the request aside and forget about it.

The message template goes into the top-level performance reviews folder, and the list goes into the person’s folder. If you want to be tricky, you can put the list in a CSV file to make it easier for a mail merge. You may generate a lot of e-mail performance feedback requests as part of this process. I’ve automated this over the years.

When you receive the feedback, save a copy of it to the folder.

If your company does not include self-evaluation as part of the review process, you may ask the people you review to do that for you. If you are unsure what to ask, use your company’s career pathing rubric for their job/level. Ask them to compare themselves to the rubric and give examples of how they have met, exceeded, or missed the expectations. If you use individual goals or OKRs, they should talk about how they achieved or missed them. They should also talk about the areas they want to improve on for the coming review period.

You want them to complete their self-review early enough that you have time to follow up with them or others on anything that comes up in that document. Your company will set the dates for you if it includes self-review as part of the review process.

Save the self-evaluation to the person’s folder.

A critical part of the performance review is reviewing the actual value the person created for the customers and company. A portion of your performance review as a lead or manager covers what your team achieved. Think through your teams’ accomplishments and think about how this person contributed to or detracted from those projects. Add concrete examples to the notes document.

Look over the person’s commits to the code of the project. Did they review others’ code? Did they contribute helpful comments? Did their code require many fixes? Did they contribute to the project documentation? Look over their comments in your project and bug tracking systems. Did they contribute helpful information? Did they help others?

It can be very tempting to try to be “objective” when looking at work output. Counting lines of code produced, number of commits, number of issues filed or closed, or story points completed might seem like unbiased data. Avoid this temptation at all costs. People have different approaches to knowledge work. Even if your team has strong guidelines on how work should be done, people will always have methods that your seemingly objective process might miss. Instead, focus on the value they contribute to the team and watch in the peer feedback for what they contribute that won’t show up in the source management or issue tracking systems.

Save your observations on their work output in your notes document.

If the person is a new hire and is still eligible for a performance review, you will use this process, but just for their time in the company. You will have to make allowances for their onboarding and focus more on how they learn to contribute than on their actual contributions.

If you are a new manager to an existing team, spend as much time as you can with the prior manager to understand how they have approached each person’s development. Read the reviews for each person before talking to the manager. If the manager has left the company, you can still reach out to them. Hopefully, they will still want the best for their old team. Depending on how long you were in the team during the review period, you may need to emphasize the peer review component more than you would have otherwise. Be aware that changing a team’s manager is very disruptive to the team. You will only have seen the results of that disruption and how the team now works.

If the person joined the team from a different group in the company, consider doing a joint review with their prior manager to cover their work before joining your team. If that doesn’t seem necessary, you should still have an extended conversation with their former manager after going over the person’s previous reviews.

It is! It should be. It is important stuff. Think about the best reviews you have received from your current or former managers. Not just the performance reviews that were the most positive, but the ones that made you feel like your manager cared about your development. A good review inspires you with the knowledge that your manager and the company recognize the worthy work you’ve done. You know that your areas of improvement have been considered and are essential for your career development.

A good review requires good data. Therefore, it is incumbent on you to make sure you are going over as much as you can, not just what you can remember at the end of the review period (also known as recency bias).

The first time you go through this process, it will take a great deal of effort, but the payoff will be worth it. For the next period, you will learn to collect and organize this data as you go. If you assemble and categorize data all the time, it will be helpful in your one-to-ones as well and not just at performance review time.

Now that you have assembled your data, you can evaluate the data against the expectations of the role and level. I will discuss that in the next part of this four-part series.

Thanks to Laura Blackwell for editing assistance

A former co-worker reached out to me recently. They are a director of engineering at a midsize startup and just got their first headhunter inquiry for a CTO role. Having never been in the role before, they wanted to know what the position was like and how to prepare for the interviews.

I realized that while there are some books on technology leadership careers, there aren’t many resources explaining the most senior levels. My goal is to provide some insight and advice for those interested in someday becoming a CTO.

I’ve worked at a hundred-thousand-person company, seed-stage startups, and many of the variants in-between. I started as a developer and followed a traditional path of moving up to more senior levels on the development track and then moving to lead, engineering manager, director, VP, and now chief technology officer. I’ve been the CTO at three different companies in two countries and three parts of the technology industry. I’m part of a few networks where I meet and talk with CTOs of all sizes and stages of companies.

I’ve learned that one reason there isn’t a good reference for the role of the CTO is that the size of the company and the expectations of the CEO define the job. Some of my role expectations and responsibilities are like those of many of my peers at similar-size companies. However, there are also significant differences in our expectations from our executive peers and boards.

Because of the variability of the role, I will broadly share my direct experiences, joined with an understanding of the expectations of other CTOs that I know.

At earlier stage companies, the CTO is often the technical co-founder. They are likely the developer who built many of the earlier versions of the software and helped hire the original development team. Their responsibilities are primarily technical: driving architecture, doing advanced development tasks, and creating technical vision.

Frequently, the first CTO of the company is hired for their ability to code and not their ability to grow or manage a team. Depending on the person, they may also lead the development team. Still, often the team’s management will eventually move to another person, an experienced manager, who may report to the CTO or be a peer to them.

The early-stage CTO is the leading technical voice for the company externally, especially if they are a co-founder. They talk to investors and potential partners and meet with potential vendors. If they also manage the development team, they will solely represent engineering in the senior leadership team. As a result, they will have responsibility for the decisions made by the engineering team. Nevertheless, if they do not manage the team directly, they might not be involved in the decisions around the day-to-day operations.

A mistake that inexperienced founding CTOs often make is that they don’t understand their role beyond coder-in-chief. They focus solely on the technology and are not active participants in the company’s leadership. As a result, they do not work cross-functionally. CTOs fixated on the how without the why or what will not be in the role very long once the company grows.

If they have no experience leading an engineering team or organization, the early-stage CTO will be challenged to grow with the company. If they cannot scale, eventually they will end up in a subordinate role reporting to a more experienced CTO hired to replace them.

Once a company reaches a size at which it needs new processes and structures, the scrappy leaders who helped get the company off the ground are often replaced with more experienced leaders knowledgeable in taking companies through the next growth stage. If the CTO hasn’t grown into the larger role, they will be part of that replaced group.

The midsize company CTO is a full-fledged executive team member working cross-functionally and meeting with partners, investors, and customers. Frequently, the midsize company CTO will also manage the engineering organization. The CTO is responsible for setting technical direction, making sure good architectural decisions are being made, and establishing best practices and working methods. They are still expected to have good technical depth, but don’t often actively contribute to shipping code. A red flag for me personally is seeing a CTO role description where the expectation is to lead a 50-plus-person organization while also actively coding on the product. It means the executive team does not have appropriate expectations for the role.

A midsize company CTO spends significant time establishing culture and practices for the teams they are responsible for; they are also very directly accountable for the organization’s decisions and its track record of delivery. The CTO meets internally with members of the other functions, such as sales, marketing, HR, and finance, to share direction for the organization and get feedback. The CTO is responsible for the administration of the teams, including the budget.

The CTO is also responsible for hiring, performance management, and team structure and may be very active in their teams’ recruitment and interview processes, especially in a scale-up type of company.

A CTO leading a more extensive development organization must be a generalist, understanding different roles and responsibilities. Their remit may include Corporate IT and Technical Support. In some companies, they may also manage the business analytics, security, product, and UX teams. A CTO who is too focused on the areas closest to their background or does not respect non-coding functions will not succeed.

As a midsize company CTO, you will often spend as much time with your peers and their teams as you spend with your own. As a result, you will need to learn about their functions and how your teams can work together. CTOs who “stay in their lane” will not be seen as an equal member of the senior leadership team and may lose their say in decisions that affect the organization.

It is very unusual for someone to move into a midsize company CTO role without having some experience leading a multilevel-development organization and working with other business functions.

If you are a manager or a manager of managers with the goal of being a CTO, there are a few things you can start to focus on that will help you on your path.

Offer to sit in on sales calls, on user research interviews. Try to understand the company’s financials when the CFO presents them. If you can’t, make a friend in the finance team and ask them to explain them to you. Understand the KPIs not only for your team, but also for the teams around you.

Get recommendations of reading or conference talks from your peers in the product, UX, and marketing teams. Think about how their work influences yours, and yours influences theirs.

If you lead an area you don’t have personal experience in, approach the people in that function with respect and a genuine desire to understand their work. They want to help you know what they do and how they do it.

Hopefully, you are already working on deepening your skill as an engineering manager or director, but are you trying to understand the bigger picture? Read other companies’ (public) handbooks, engineering blog posts, and conference presentations about their ways of working. What practices are interesting? Which can you try in your team? How do you think they will scale, or what issues do you think they may have?

The best way to learn the job is to do the job. Even better is having someone who is already doing the job explain to you how they perform it so you can help them.

The main difference between the expectations of line managers and senior managers is the emphasis on strategic thinking. Executives contribute to the company’s strategic planning and use their understanding of the company’s goals and the current situation to make sure that their teams are setting up the conditions for the company’s success. Strategic thinking is a learnable skill, but it takes practice.

Being a CTO was not what I imagined it to be when I first decided it was my career goal. It is a lot of work, carries much stress, has fewer perks than you might think, and can be somewhat lonely. However, it is also the most personally rewarding job I have ever had. With the challenges, there is also incredible responsibility, tons to learn, the ability to influence the company’s direction, and the chance to affect the lives of dozens or hundreds of people on your team. I have yet to regret my choice to pursue this role.

Thanks to Laura Blackwell for editing assistance

I have never heard the word “politics” used in a positive light when describing a work situation. On the contrary, the words “corporate politics” evoke memories of cynical executives in ’90s movies quoting The Art of War to their reports while figuring out how to undermine their peers. One of the Merriam-Webster dictionary’s definitions of the word is “political activities characterized by artful and often dishonest practices.”

I propose that we reconsider the word “politics,” especially when used in a work context. The word, and the techniques ascribed to it, are inherently neither good nor bad. You can use politics for ill intent or good. Good intention aims for a win-win solution, whereas bad intent aims for a win-lose solution. Instead, let’s use this Merriam-Webster definition for the word “politics”: “the total complex of relations between people living in society.” For our purposes, let’s call the company we work in our society. A company is a society in that it can have a panoply of personal relationships, group dynamics, shared goals, and systems of governance.

If we can get over our initial reaction to being political, how can we use some of these techniques for win-win solutions to problems?

Thinking politically means thinking ahead (being strategic), understanding the motivations of the people you need to convince (having empathy), and understanding the interactions of the systems you are trying to influence (systems thinking). You are working to make something happen-something you cannot do on your own. You may be working to overcome resistance to a new idea in a conservative institution. You could be trying to persuade another group to help your team with a project that will be good for the company but might make that group miss their quarterly goals.

Thinking politically will help you gain support for your ideas, soften resistance to change, and focus people on the bigger picture. If you improve everyone’s situation, your peers will appreciate you, and you will find the way forward easier in the future. Conversely, done poorly, where you or your team move ahead at the expense of others, you will find it increasingly hard to gather support in the future.

In the early days of the public cloud, I worked in a company that already had established data centers worldwide. Getting a new server racked meant requisitioning a server from the central IT organization, following all their guidelines around the machine’s configuration and which technologies could be used on it, and giving them access to maintain and manage it. The process to get a single server going with a public-facing interface could take months.

I was leading a new team trying to incubate a new product. We had adopted a Lean Startup approach, moving to get to market in under six months. As this was a brand-new area for the company, we couldn’t be sure how quickly the public would adopt the product, and we wanted the ability to add capacity quickly if needed or shut the project down if it wasn’t getting traction. The company’s lead time for servers was not going to work for us. So, we decided to leverage Amazon’s young AWS offering. I knew that this would be a controversial decision and might incur opposition from other teams, especially IT. I could have chosen to “ask forgiveness, not permission” and hope that my small team could fly under the radar long enough to launch, but that was very risky. Our actions could be interpreted as a deliberate avoidance of company security and budget policies, which could prevent us from launching if we were found out.

I spoke to my peers in other teams to understand their prior experience working with the centralized IT team. I learned that if I approached the IT team directly for permission to use the public cloud, I would get an immediate “no.” That would put me in a position of having to get their decision overruled, which would take a lot of time and energy. I decided to go a different route.

I put together a presentation on our plan for our product. I included our quick path to market to mitigate risk for the company, our plan to leverage the public cloud (to scale quickly and manage cost-effectively), and how we would address any corporate security concerns. The goal of the presentation was to build trust that my team was thinking about the business and not just playing with new technology, and to show that we had answers to the issues I expected other groups to raise. I portrayed our product plan as an innovative experiment in new product development; a low-risk approach to moving faster as a company. I wanted to get some protection for my team at a level that would short-circuit other teams worried about this new way of doing things.

After working with my boss to ensure I had their unequivocal support, we got time on my SVP’s calendar to discuss the plan. I prepared for any argument against the plan, but I also left room for input from the SVP to help them feel invested so they would help protect the project. We left the meeting with approval for our approach and moved forward quickly enough to launch the product within our six-month window.

The product was more successful and grew more quickly than we had planned. Our public cloud adoption made it far easier for us to scale as the number of our customers did. Our success also increased our visibility within the company, however. The teams invested in managing and growing our worldwide data center infrastructure now started to see us as a threat. I began to have many increasingly tense meetings with them to discuss moving into the corporate infrastructure. I could have used my product’s success to force the other team to back off, but that would have created even more enmity, setting up our teams for friction forever.

Instead of using my team’s success as a wedge to ignore the IT team’s demands, I worked with them to understand why we had to make the decision we had. I also identified what they could do to make switching to the internal infrastructure an easy decision for us and for other teams

considering following in our footsteps. I committed my team to switching to the company’s infrastructure as soon as it could support us.

Reading through that experience, you can see several political maneuvers I used to get my team the space we needed to ship our product.

If I had stopped at this point or pressed my new advantage over the IT team, that would have been the type of corporate politics that people despise. I would have created a win-lose situation (and some very angry co-workers who would have justifiably felt I’d wronged them).

Instead, I took the following steps to help the group I felt I had to work around and improve the situation for everyone at the company:

Making sure we helped the IT team was more work for my team, but it was better for them and the company at large. It made the solution a win-win.

An outside observer, especially a jaded one, could look at each of my actions in a very different light. That observer would say that I schemed to isolate the IT team, skirted appropriate behavior, and cheated by going over their heads. If I hadn’t then gone back to help lift the IT team, I might agree.

One might say that the best thing to do would have been to work with the centralized IT team to convince them that they should allow and support my plan. I would agree with that sentiment if it were possible to gain the IT team’s support and ship my product on schedule. However, the experience of my peers told me otherwise. Those who have worked at large corporations with siloed functions working against different goals understand how intractable those other groups can be.

When faced with a challenge at work, try to understand the motivations of the people you work with and the systems they operate within. From there, build a strategy to achieve your goal. If you can achieve your goal while helping others move towards theirs in the long term, you will be an innovator and a team player within the society that is your company. On the other hand, if you achieve your goal at the expense of others, you will be nothing more than a player of the unspeakable p-word.

Thanks to Laura Blackwell, Hannah Davis, and Mandy Mowers for editing help.