This article is part three of my series on writing valuable performance reviews. The first part is about preparing for the evaluation. The second article discusses writing the appraisal. This piece will help you make a fair raise recommendation. The final part gives you tips on delivering the review.

Determining compensation is a crucial part of performance management. I fully believe in the Autonomy, Mastery, and Purpose trio for motivation outlined in Daniel Pink’s book Drive. However, experience has shown me that even people who have all three of the trio still expect performance in their role to result in more significant compensation.

Aside from hiring or firing an employee, compensation decisions are the most important decisions a manager can make. The decision is significant because the basis for next year’s compensation is this year’s, especially if you stay at the same company. A manager’s mistake in remuneration can result in a significant difference in lifetime salary for someone. Therefore, the compensation change recommendation must be highly considered and fair.

In some companies, the manager creating and delivering the performance review has little input in the compensation decision. If this is your situation, it is still helpful to understand how salary works at other companies, since you may hire people from those places. It is also beneficial when you are responsible for that decision after a promotion.

How does the compensation process work?

Many junior managers have unrealistic expectations around what can be done with compensation because they don’t understand that it is part of the greater corporate budgeting processes. As a result, they imagine an infinite pool of money to draw from for raises.

Every company does its budget and compensation processes differently, but there are common aspects across all the companies I have worked at. One generally true statement is that larger companies will typically be more fixed in their processes and make exceptions infrequently.

The compensation budget is part of the larger company budget, which is agreed upon with the board of directors at the start of the year. An essential measure of the ability of the senior leadership team is their capability of working within the constraints of this agreed-upon budget. This budget objective means that at the most senior levels of the company, someone is keeping an eye on the total salary budget for your organization and will work very hard to make sure that it is not over budget. There is a target salary budget for your team based on the team’s current salaries and the board’s agreed-upon raise budget as a delta.

Your manager will recoup the difference from another team if they allow you to go beyond that budget. Does this mean you shouldn’t go over budget if it is warranted? No, but it means you need to have realistic expectations about what is possible.

To avoid the budget constraint challenges, line managers in some organizations do not have salary recommendation responsibility.

If you can make salary recommendations for your team, how does the procedure generally work?

You receive:

- your teams’ current salaries and some indication of what their most recent raises were,

- an idea of the overall budget target for the organization (usually presented as a percentage delta on existing salaries),

- the salary bands that individuals are currently in, and

- some guidance around the process (possibly including some default raise percentage for different levels of performance).

If you don’t receive all this information, you should request it. It is vital for the decision-making process.

You make an initial recommendation for each team member, which you send to your boss. Your manager combines your proposals with those of your peers, adds in their own direct reports (including you), massages the numbers somewhat, and passes it to their boss, who does the same. This process continues to the CEO.

A few weeks (or months) later, you receive the final salary numbers for all your reports to communicate to them, either as part of the performance review or separately. Sometimes the numbers are identical to those you recommended; sometimes they are different. Sometimes your boss knows why the numbers are different, and sometimes they do not.

Equity (stock), bonuses, and salary serve different purposes as part of a compensation plan.

Salary is just one part of a compensation scheme; stock, bonuses (if your company has them), commissions (usually only for the sales team), and benefits are all part of how a company attracts and retains its employees. Each of these elements has a different purpose.

Salary is a direct measure of employee performance. It is to reward someone for doing a good job. Employees who are “high performers” are paid more than others in the role whose work isn’t as valuable.

Equity, in the form of stock grants or options, is usually seen as a measure of employee potential. Since these vest over time, they are an incentive for an employee to stay longer. Therefore, you want employees who have a high potential to stay and grow at the company. Some companies also use equity to offset salaries, since the immediate cost to the company is less.

Benefits are often overlooked because they are given equally to all employees, but they can be vital to employee retention. For example, if an employee is interested in developing their skills, letting them know that the company can pay for additional training is a significant statement and may counterbalance a raise that they are not happy with.

When making recommendations around employee compensation, take all the aspects of your company’s compensation plan into account. Different elements will be more important at various times to your employees.

What about fixed compensation systems?

Some companies, notably Buffer and Gitlab, have adopted fixed formula models for employee compensation and transparency about those models. Company founders designed these models to be fair and reduce bias. I think there is a lot of potential in these models, and the people I know at companies that have them are fans.

Typically, the companies that do fixed compensation systems adopt them very early (instead of switching to them later). The companies are transparent about their compensation, which is critical with a nonstandard model. As such, people generally self-select into those companies. The mechanics of switching to that model seem very difficult to me.

It is worth paying attention to companies using these systems to see how they scale and grow and see if they become the norm.

What is the right raise for someone?

The significant part of the fixed compensation systems is that they take the bias and subjectivity out of the raise decision. The bias is all built into the decisions that created the original model. You should strive to be objective and fair for the more standard processes. You should validate the reasoning you use with your manager and peers to ensure that the organization uses a consistent rationale.

Start with their current salary.

Where is the person’s current salary within the salary band? Does that current salary make sense, given their past performance? Has the band gone up significantly since the last salary review period? Where do they sit relative to their peers in the same role/level doing similar quality work?

Now think about their performance since the last salary review.

Are they meeting your expectations or exceeding them? Not achieving them? What has been their trajectory over the last few periods? Are they gaining momentum? Losing it?

Is the person being promoted?

If you are promoting the person, you should be gauging them against the bands for their new level. Unless the promotion is long overdue, or the person was very highly paid relative to their peers in their previous level, they should be coming into the lower part of their new salary bands. Placing them in the appropriate spot in the salary band gives them ample room for raises as they grow into their new responsibilities.

Now, look at the target percentage for the organization.

Some of your team should be over that, and some should be under. Your boss will tell you if they expect you to achieve a budget target or not. Even if you anticipate not to come in exactly on budget, you shouldn’t be wildly off it. Now, based on the target budget, the person’s current salary, and their performance, put in your initial number for them.

If you aren’t given a spreadsheet with your team’s numbers, you should create one.

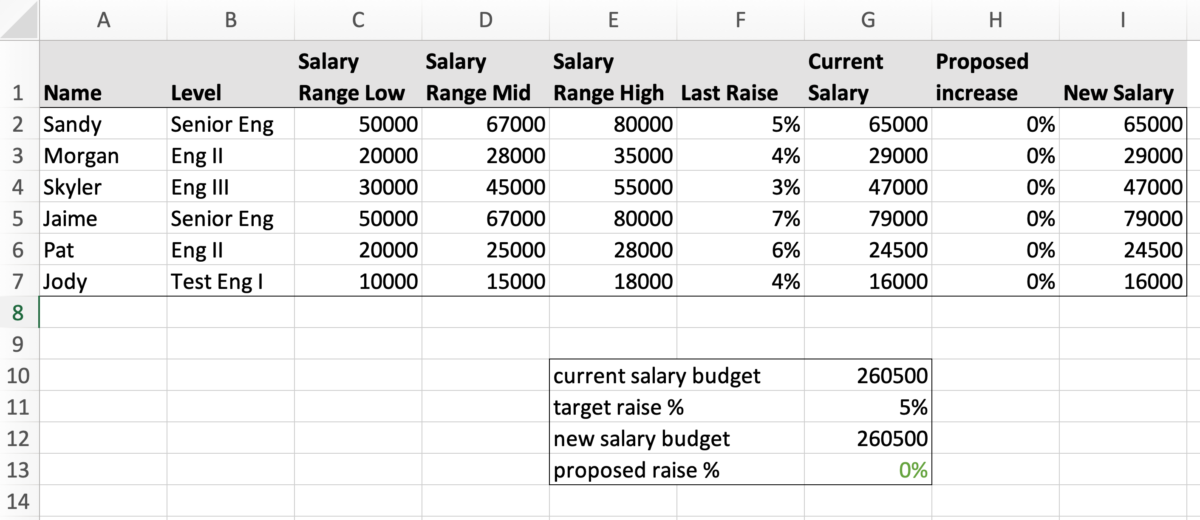

I generally have something like this (and create it if I don’t get one from the HR team).

A spreadsheet helps you look at your recommendations for people relative to one another, and it enables you to understand what you regard as the target for your team.

As you figure out your initial recommendation for each person, enter it into the spreadsheet.

Don’t pay attention to any of the other data while you do this. If it helps, you can hide any rows or columns that you are concerned may throw off your judgment. You can also enter it into another tab if you prefer.

After you have done your first-pass numbers for everyone on your team, you can see where you are relative to your budget. You should also look across the team to ensure you are using consistent logic. It is better to look at percentages rather than salary amounts at this stage. Are the overperforming people relative to your career rubric getting more significant raises than those underperforming or merely meeting expectations? Are the raises going to underperformers in alignment with their performance?

One way to approach this is to think about the raise conversation relative to the performance conversation. Are you saying the same thing with both? For example, a sizeable raise completely blunts a stern message to someone underperforming. Similarly, a slight raise blunts any positive message in the performance review for an overperformer.

If the raise percentages seem fair, look at the budget total.

Are you over budget? If you are over by a relatively small amount, and your manager has not asked you to be right on target, you may be ready to show them the numbers for their input. On the other hand, if your manager has asked you to be right on budget, then you will need to make some adjustments.

There are several things you can try to reduce the overall amount.

If you are significantly over budget, you can use one or more of several techniques for bringing your numbers down.

You may reduce all the raise recommendations by a fixed percentage amount.

Applying the same amount of reduction to all your recommendations keeps them the same relative to one another.

Instead of giving small percentage raises to underperformers, consider reducing them to zero.

If someone is significantly underperforming, recommend no raise rather than giving them an insubstantial raise. Receiving no raise will ensure a difficult review conversation, but it will reinforce the underperformance message.

Decrease individuals’ percentages to achieve a rounded salary number.

When given their new salary information, people will look at the percentage and the new salary number and remember one of them, the salary. They won’t recollect the exact wage; they will round the number in their heads. Take advantage of that to get some extra headroom.

Let’s look at one of our fictional employees, Sandy. Sandy has done very well this year, and you want to reward them with a big raise. Your first idea is a 9% raise, which will give them a new salary of 70,850. After doing the rest of the raises, you are more over budget than your manager is OK with. Since Sandy is your second-highest paid employee and is getting a big raise, you can give them a slightly smaller amount, and they will likely not miss it. Instead, if you gave them an 8.46% raise, that would give them a new salary of 70,500 (a nice round number), and it would save you 350. If you needed more room, 70,250 or even 70,000 are still big raises from their initial 65,000, but are only minor percentage differences from your initial idea.

Robinhooding helps you give more significant raises to lower-paid employees.

The rounding trick I mentioned above is also helpful if you work against budget constraints, but you want to give more significant raises to those on the lower end of the salary spectrum. A small percentage change for a well-paid person can be a very substantial percentage change for someone who is less well-paid. I call shifting small percentages from higher-paid to lower-paid employees Robinhooding.

If you are under budget, should you increase your raises?

The answer to this question will depend on your organizational culture and norms. If this is your first time making salary recommendations, you might ask your manager for guidance. If all your peers come in over budget, and you are under, you may either look fiscally responsible, overly critical, or like an obvious place to find more funding for your peers’ excesses. You don’t want your team to suffer for other managers’ inability to meet a budget.

If you are significantly under budget, you may want to reexamine your recommendations, as this would indicate a seriously underperforming team.

Once you are happy with your overall recommendations from an individual and budget perspective, take one last look at them before submitting them to your manager.

Are your recommendations saying something you do not intend? For example, is there one group getting the majority of the large or small raises? Look for your own unconscious biases appearing in the numbers. Once you are fully satisfied that your recommendations indicate the performance of the individuals on your team, submit them to your HR representative or manager for the next phase of the process.

What happens next?

Your manager may want to review your recommendations with you, or with you and your peers together. Your manager must ensure that each report uses consistent guidelines for their recommendations. They may do this independently or may pull all their manager reports together for a more extensive session (at a previous company, we called this the “Battle Royale” ).

Come prepared when it is time to review your recommendations with your manager or peers. Preparation should not be problematic if you have followed the recommendations from the previous articles. The more concrete examples you can provide to justify your proposals, the better.

Your manager will incorporate the input from you and your peers into a larger version of your spreadsheet. They may need to modify some of your numbers to make their numbers work. Your manager will then do a similar review with their peers, and it will go up the levels of the organization, potentially to the senior leadership team. The more information you give your manager, the easier it will be for them to preserve and defend your recommendations. The information you provide them will also give their manager more information.

Once there is agreement on the salary changes for the organization, the finance team updates the numbers in the payroll system. You then receive the final numbers to pass on to your employees.

I discuss the salary and performance review conversations in the following article.

The four parts of this series are:

- Assembling the data

- Evaluating the data and writing the review

- Making salary recommendations (this article)

- Delivering the review

Thanks to Laura Blackwell for editing assistance