Practical Lessons in Organizational Design

Introduction

Most engineering leaders inherit organizations they didn’t design. By the time we step into a role, the structure is already there: a mix of teams, reporting lines, and legacy decisions. It’s easy to accept that structure as “just the way it is.”

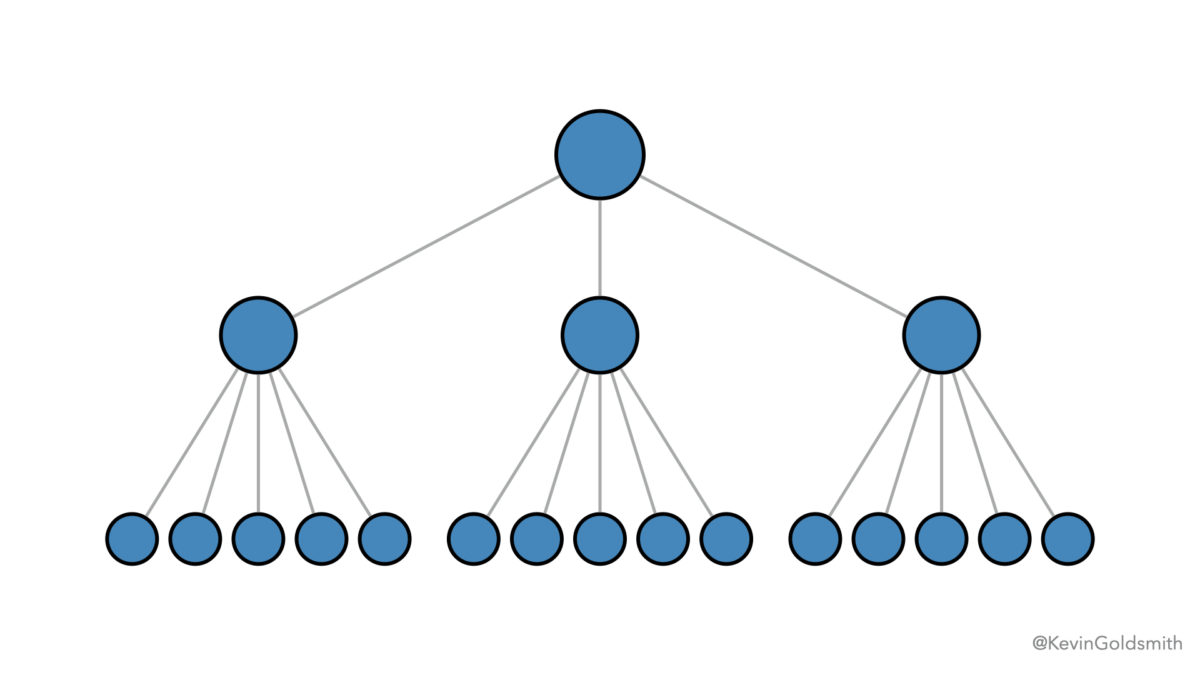

But structure quietly shapes everything. It defines how information flows, how decisions get made, how accountability works, and how fast (or slow) a company can move. The org chart isn’t just a management artifact; it’s a piece of system design.

Over the years, I’ve learned that organizational design is one of the most potent tools a technology leader has, and one of the least understood. You can’t manage around a broken structure any more than you can code around a broken architecture.

Inheriting the System

I’ve only had a few chances to design an organization from scratch, usually in early-stage startups. More often, I’ve inherited something that had evolved over time. Some were the result of thoughtful planning. Others grew like weeds.

Every organization reflects its history. Even the most ad-hoc structure is an artifact of past decisions: who talked to whom, what problems needed solving, what crises shaped the company.

That’s Conway’s Law in action: organizations design systems that mirror their communication structures. Look closely at a product’s architecture and you’ll see its org chart.

In the product engineering organization I led at Adobe, my teams were arranged by function: one group focused on building the backend, while others managed clients, core libraries, and infrastructure. This was the standard team structure at the time, but it limited our speed. Each feature had to go through four different teams, each operating on its own sprint cycle. As a result, it could take months to ship a simple feature because it needed to pass through each layer of the teams.

When I joined Spotify, the structure was entirely different. Autonomous, cross-functional squads owned features end-to-end. They deployed independently and moved fast. The system’s modularity came directly from the team design.

Different problems, different structures. Both logical in their contexts, but the lesson is constant: you ship your org chart.

Designing for Purpose, Not Precedent

Too many companies treat organizational design like a template. Someone says, “Let’s use two-pizza teams like Amazon,” or “Let’s adopt the Spotify model.” The intent is fine, but the context is missing.

Amazon and Spotify built those systems because they fit their culture, strategy, and scale. Copying the form without understanding the function is like cloning another company’s codebase without knowing its dependencies.

The real question isn’t “what structure should we have?” It’s “what problem are we solving, and what design will align our teams to solve it?”

Structure is strategy made visible. A good design aligns incentives, communication patterns, and ownership boundaries with your goals. It creates high-bandwidth communication where you need it and separation where you don’t.

And it has to evolve. The organization that works for a 20-person startup will break at 100. The one that works at 500 will creak at 2,000. Like software architecture, organizational design is never finished.

Diagnosing What’s Broken

You don’t redesign an organization because it’s old. You redesign it because something isn’t working.

My favorite diagnostic tool is simple: follow the work.

Take one feature or story and trace it from idea to production. How many teams does it touch? How many handoffs? How long does it sit idle?

Every delay is a clue. Sometimes it’s a resourcing issue. Sometimes it’s a missing skill in a team. But often, it reveals deeper misalignments: unclear ownership, too many dependencies, too little trust.

At Adobe, that exercise made the bottlenecks obvious. Each feature touched four teams in sequence, and a “simple” change could take three months due to the handoffs. At Spotify, where squads owned the full stack, the team shipped the same kind of work in a single sprint. It wasn’t magic. It was designed.

If you want to understand why your organization feels slow, follow the work.

Lessons from Team Topologies

If Conway’s Law explains why structure and systems mirror each other, Team Topologies by Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais gives you language for designing around that reality.

They identify four core team types:

- Stream-aligned teams own a product or flow of work end-to-end.

- Enabling teams help others improve tools or skills.

- Complicated subsystem teams handle specialized areas of expertise.

- Platform teams create shared systems that reduce cognitive load.

They also describe three ways teams interact: collaborate closely for a time, provide something as a service, or facilitate learning.

The value isn’t in the framework itself; it’s in the vocabulary. It helps leaders think about flow instead of hierarchy and design structures that reduce friction instead of adding layers.

When I read Team Topologies, I recognized much of what we’d already been doing at Spotify; the authors had spent some time at the company. But I also saw patterns from earlier roles that suddenly made sense in hindsight. The book doesn’t prescribe. It clarifies.

Common Patterns and Traps

Most organizations follow predictable patterns as they grow.

Functional silos work early but become brittle later. They make coordination explicit but slow.

Cross-functional teams increase autonomy and speed but come with a higher cost. At Spotify, that meant hiring more mobile developers than most companies would ever consider. It worked because the company optimized for velocity over constraining headcount.

Centralized data or infrastructure teams start strong, then evolve into bottlenecks. You have to anticipate when to distribute those capabilities.

Matrix organizations can preserve continuity and reduce disruption when people change teams, but they also add complexity quickly. They work best when accountability is crystal clear.

And then there’s the most common anti-pattern: designing around personalities. Building an org around one person’s strengths, or avoiding their weaknesses, might seem practical in the short term. It always becomes debt later.

Reorgs as Refactors

When a structure stops working, treat the reorg like a refactor, not a revolution.

Don’t blow everything up. Make small, deliberate changes. Be transparent about what you’re solving and how you’ll measure success. Make the problems you are trying to solve clear, and how you will handle the case where the structure change doesn’t solve them.

The biggest mistake leaders make is reorganizing at people instead of with them. Change feels arbitrary when the reasoning is hidden. If people understand the problem, they’ll accept the solution even if they don’t love it.

Every reorg has a sociotechnical cost. You’re not just moving boxes. You’re changing relationships, communication paths, and identity. Handle it with clarity and care.

Reorgs should feel like system refactors, not revolutions.

Leading by Design

Organizational design isn’t a one-time project. It’s an ongoing act of leadership.

Start by mapping your current system: who talks to whom, where decisions stall, and where ownership is ambiguous. Align the structure with your strategy and your culture.

Design for clear interfaces between teams and between roles. Iterate carefully, explain your reasoning, and gather feedback.

The structure that got you here probably won’t get you where you need to go—and that’s okay. Good organizations, like good architectures, evolve.

If you drew your company not as boxes and lines in a directed acyclic graph, but as flows of information and work, what would it look like? Where would the friction be? Where would it hum?

That picture, not the official org chart, but a system diagram, is the authentic architecture you’re building every day.

To hear an extended discussion of this topic, please listen to my podcast episode: https://itdependspod.com/episodes/the-hidden-architecture-of-engineering-practical-lessons-in-organizational-design/

For more about Conway’s Law and my experiences utilizing it in organization design, see the video of my talk Architecture and Organization.