I was in San Francisco in December for a conference. While I was there, I ended up connecting with a couple different companies who have been inspired by Henrik Kniberg’s whitepaper on Scaling Agile at Spotify, and who have been trying to implement some of those ideas in their own companies.

I think Henrik’s paper does an excellent job on describing the what and how, but it seems that the “why”, and some of the critical ideas can get lost when others read it.

If you haven’t read Henrik’s white paper, I’d suggest that you read that before reading the rest of the blog post. I will do a quick recap here though.

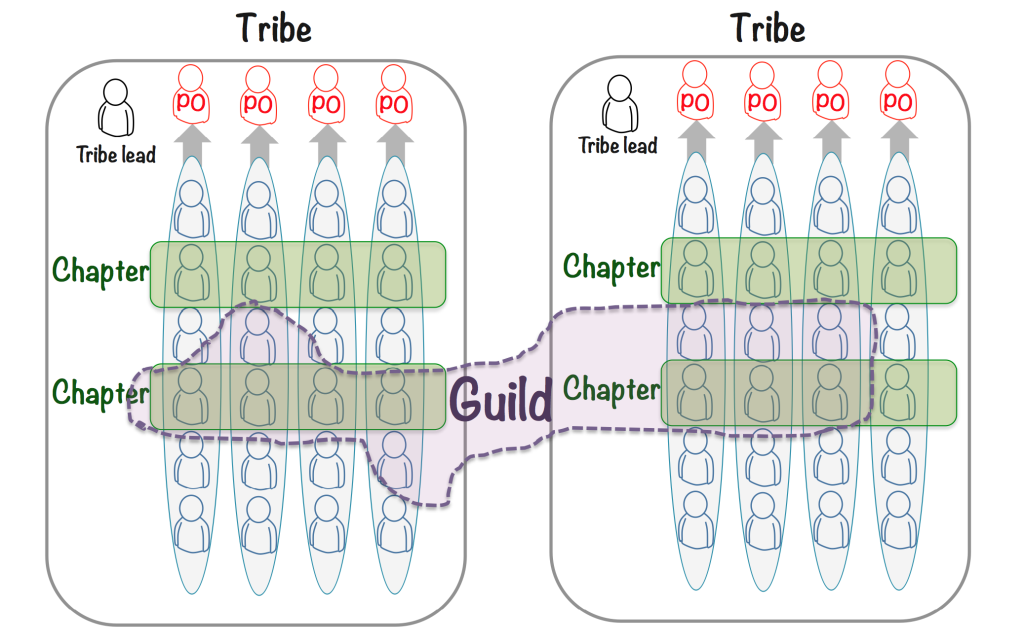

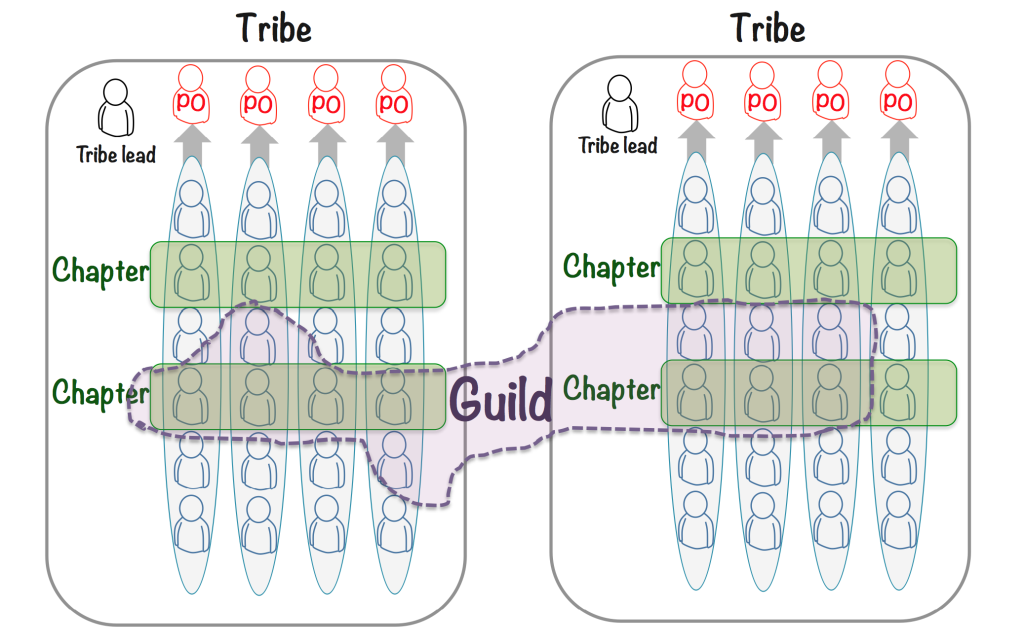

Spotify’s engineering and product organization (now over 600 people) is split into several large groups called Tribes. Each Tribe is responsible for a set of related features or engineering functions. For example, our largest tribe is the Infrastructure and Operations Tribe, whose name is pretty self-explanatory. I am the Tribe Lead of the Music Player Tribe. We handle importing audio from our label and distribution partners, storing and streaming the music, search, collection and playlists, artist pages, music metadata and the music knowledge graph that supports things like the above, but also ads, discover, radio and the like.

While the whole company works on the same product, Spotify, each tribe is set up so that it can work as independently as possible. As you will see below, a critical aspect of our organizational model is to give autonomy at every level. This helps remove decision-making bottlenecks and unnecessary dependencies, which improves velocity.

Each tribe is composed of squads. A squad is a team that is responsible for a single feature or component. For example, there is a squad that is responsible for search, a squad responsible for the AB test infrastructure, etc. As each tribe is set up to be as autonomous as possible, each squad is also set up to be autonomous. In the context of a feature development team, this means that each team is a full-stack team. A full-stack team is responsible for both backend implementation as well as the user interface implementation, on all platforms.

A typical feature squad would have web service engineers, iOS, Android, web and desktop engineers as well as testers, an agile coach, a product owner and UX designer. With this staffing, the squad has everything they need to implement anything related to their feature. They don’t have to wait on another team to implement the pieces they need. They also have autonomy and local decision-making ability, so there are few impediments on their speed of execution.

To this point with Tribes and Squads described only, Spotify may seem like a traditional, hierarchical engineering organization, but this is where the similarity ends. Unlike a traditional organization, a squad does not have a single engineering leader whom everyone on the team reports to. In fact there is not a single leader for the squad. The Product Owner and UX Designer work with the engineers and testers collectively to make decisions about their features.

Spotify is not a “no manager” culture though. We feel strongly that managers have a role in supporting the people who work for them. Managers have an important role to play as technical and career mentors and organizational communication conduits. Rather than have management hierarchies follow organizational ones (creating a de facto command-and-control structure), we instead have first level managers responsible for technical functional areas across multiple squads.

We call these reporting and functional groupings “chapters.” Again, as an example, reporting to me, the tribe lead, are Chapter Leads. In my tribe, there are currently three backend (services) development chapters, two front-end development chapters (including all the UI developers), a core library chapter, and a test chapter. These seven Chapters span eight different squads. Almost every chapter lead has reports in 2 squads, and a few of them have reports in three squads. Almost all chapter leads work within a squad in some capacity as well, either as developer or technical lead, and not necessarily within a squad that has members of their chapter.

This chapters/squads matrix organization is critical to our organizational agility. It allows the squads and the tribe to be more fluid. We can spin up a new squad to take advantage of an opportunity or handle an issue without worry about changing reporting structures. If a squad completes its goals and has no reason to exist anymore, we can dissolve it without punishing a manager. This is a very important difference to a traditional hierarchy, because it gives us a lot of flexibility and helps us avoid the old political issues around empire building and resource contention.

In addition to our Tribes, Squads and Chapters, we also have virtual organizations called Guilds. Guilds are cross-tribe organizations centered on different technical or interest areas and their membership is voluntary. The guilds serve as ways to promote cross-tribe collaboration and communication, especially around things like best practices. For example, we have guilds for Web Development, Agile Practices, Leadership, Test Automation, etc. The guilds foster developer-to-developer communication, which is one of the ways that we keep all these autonomous teams from all going off in completely different directions.

From Henrik’s paper, this diagram illustrates the organizational structure I discuss above:

I’d like to give some more background around why we have implemented this organizational model at Spotify; elaborate on our goals for implementing it, and discuss the aspects of our culture, which have been critical to its success. It is really great that other companies have been inspired by the way we work, but I think if you implement only parts of the model or try to impose it on a very different corporate culture; you will have a difficult time achieving the same level of success with it that we have had.

If you are considering using the Spotify organizational model within your company, there are a few things that will be critical to your success:

Our organization model assumes that engineering is doing development with agile methodologies. Our goals for autonomy mean that we do not prescribe any particular development framework our squads must subscribe to. However, all of squads use agile development methodologies. While we do our best to minimize dependencies between squads and tribes, there will always be some since we are all working on the same product. Any individual squad choosing to build using a traditional waterfall or other non-agile process would not be able to keep up with the rapidly changing teams around them. If they tried to impose some sort of process on other teams so that they could follow a longer-term development plan, they would start slowing down the rest of the organization.

A critical requirement in making our organization model work well is that the entire company works with and understands agile practices and processes. While our legal team isn’t doing scrum or kanban, they are used to working with engineering teams that use agile processes. Having the entire corporation understand and agree with agile means that no line of business area becomes an impediment to the speed of implementation. Think of this in terms of Amdahl’s law, applied to a development organization. If your development teams are working quickly in parallel, but marketing or legal is not supportive of an agile approach, they will become a bottleneck that will slow down the overall speed of the company.

Similarly, implementing this with just one team as a test in a larger engineering organization will be prone to issues. A traditional engineering organization is not usually set up for autonomy. Adding a single autonomous team within that web of dependencies is likely to hamper and frustrate the team and skew the results of the experiment.

While I’ve mentioned autonomy in several places already, I cannot understate its criticality. Each squad must be empowered to make their own decisions, not only on features, but also on development model, infrastructure, and implementation. Every decision that has to be approved outside the team means a delay that slows development. Each dictated implementation or infrastructure decision means that a technology that doesn’t fit to the way the team works or something new that must be learned before the team can build. This is a challenge to coordination, but in practice it isn’t as bad as it might seem. Best practices and technologies do spread from team to team through avenues like guilds. Teams adopt these practices and technologies on their own schedule or pioneer new ways of working if it makes it easier for them to deliver value to our customers and then spread their learnings to the other teams.

Trying to layer the tribe and squads model over a traditional reporting hierarchy would be very problematic. While we have many long-lived squads at Spotify, we are constantly creating and disbanding squads as new needs arise or missions are fulfilled. Squad membership will also ebb and flow as required by the needs of a squad’s mission. Traditional hierarchical organizations are self-perpetuating and restructuring them is very disruptive both to the management chains as well as the individual team members. You would gain some of the benefits of the Spotify model by building full-stack teams in a traditional organizational hierarchy, but you would lose a lot of the overall speed benefits that we leverage with our matrix organization.

In conclusion, if you are looking to improve the speed of your development and are inspired by Spotify’s organizational model, there are a few things that you need to understand. Our model works because it is layered on top of our corporate culture. Our culture values autonomy, agile processes, democratic teams, and servant leadership, amongst other things. You can certainly take some of the ideas from the way we work and apply them in your organization, but without the cultural underpinnings you may not get the same returns.

Some other references worth checking out are Henrik Kniberg’s keynote at the Paris Scrum Gathering and my keynote at the { develop: BBC } conference.